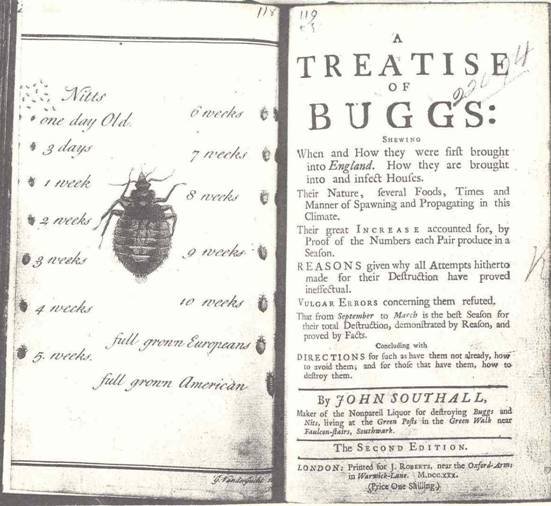

The nature of the problem is made clear enough right from the start. Bear in mind that this was published in London in 1730:

“As Buggs have been known to be in England above sixty years, and every Season increasing so upon us as to become terrible to almost every Inhabitant in and about this Metropolis, it were greatly to be wished that some more learned person than my self, studious for the Good of Human Kind, and the improvement of natural knowledge, would have oblig’d the Town with some Treatise, Discourse or Lecture on that nauseous venomous Insect.”

No-one else having come up with such a treatise, it was left to Mr Southall, our author, to write one himself. How he came to do so is an interesting story.

It was 1726, and he had not long been in the West Indies when he fell ill:

“I fell sick, had a Complication of the Country Distempers, lost the Use of my Limbs, and was given over by the best Physicians at Kingstoun in Jamaica.”

However, he recovered and whilst out horse-riding one day he came upon “an uncommon Negro, the Hair or (rather) Wooll on his Head, Beard and Breast being as white as Snow.” He had no wrinkles and still had all his teeth, and though he didn’t actually know his true age, Mr Southall estimated that he must have been at least 90 years of age.

“Whilst we were in discourse, he perceiving me often rub and scratch, where my Face and Eyes were much swelled with Bugg-Bites, asked if Chintses (so Buggs are by Negroes and some others there called) had bit me? On my answering, yes; he said, he wonder’d white Men should let them bite; they should do something to kill them, as he did.”

Further discourse, plus a bribe of tobacco and money, and the old Negro gave Mr Southall “a Calibash full of Liquor” to be applied like paint to the furniture in which the Buggs lurked. He goes on:

“Possess’d of this, well Pleas’d I went home, and tho’ much fatigued I could not forbear using some of it before I went to sleep; and to my surprise, the instant I applied it, vast numbers did, (as he had told me they would) come out of their Holes, and die before my face.”

Mr Southall swept these up and went to bed, passing a comfortable night, “not being Bugg-bit then, as I always was before.” In the morning he found that he had lots more dead Buggs to sweep up, so he was now quite convinced that he was on to a good thing.

The next thing was to get the recipe for this concoction, which he did by bribing his negro friend with some “English Beef, Pork, Biscuit and Beer, and some Tobacco”. Since some of the ingredients would not be readily obtainable back in England, he procured quantities of these to bring back with him.. He arrived back in England in August 1727.

Mr Southall thereupon set up in business, and entered upon a prolonged series of experiments on Buggs and their breeding habits. These experiments, which were aimed at finding out how to use this concoction to the greatest effect, need not concern us here, though it was news to me that Buggs first appeared in England in the new houses that were built just after the Great Fire of London. Apparently they were brought in with imported “Firr-Timber.”

Mr Southall called his concoction “Nonpareil” and told the readers of his booklet: “you may have a bottle for 2s, sufficient for a common Bed, with plain Directions how to use it effectually.”

He would also, for a fee, come to your house to do the necessaries “if the trouble of doing it yourselves be disagreeable to you.” Or, if he didn’t come in person, he would send one of his servants round. Either way:

“To clear a Bed-sted with Moulding Tester, Wood Head-Cloth, Headboard and its Furniture, 10s 6d.”

Incidentally, if the application of the liquid damaged the furniture (for it was, by his own admission, “strong and oleous”), he would pay compensation.

What became of Mr Southall and his business, I have no idea. Only his booklet survives to tell his story.