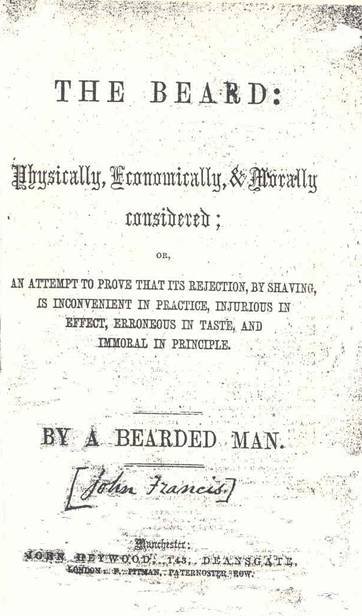

Mr Francis begins by admitting that the subject of beards may be deemed trivial by some, but within a paragraph he has brought the subject to one of theological proportions:

“If our Maker willed that the male countenance of mature age, should be set-off and embellished with what is called a beard, and which certainly gives to it a most distinctive character; is not the rejection and removal of that beard an unmistakable vote of censure on divine wisdom? and on the other hand, if the beard is prized, valued, and thankfully cherished, is not this an act of obedience, calculated to confirm our respect and veneration for all the laws of God, and to increase our faith that in him ‘we live, and move, and have our being’?”

Not only that, but there’s the aesthetics of the thing:

“We admire the mane of the lion, the tail of the peacock, the antlers of the stag, the spurs and gay plumage of chanticleer. Why then deny the noblest creature his beard?”

After some further preamble about tattoos, corsets, pierced ears, and wigs, Mr Francis restates the propositions of his title-page, namely:

“That the rejection of the beard by the custom of shaving, is inconvenient in practice, injurious in effect, erroneous in taste, and immoral in principle.”

Under the heading of inconvenience come the journeys to the barber (there and back!); waiting one’s turn; and the time actually spent in the chair. If one shaves oneself, there is the messing around with hot water, lather and strop, not to mention the sharpening of a blunted razor and the patching up of the scratched cheek and bleeding chin. Reckoned up nationally, Mr Francis says, 104 million hours per year are spent in shaving – equivalent to the aggregate labour of 33,440 men working a ten hour day. The total cost of visiting the barber once a week, or of buying the razors to do the job oneself, amounts, nationally, to about £3 million.

Under the heading of injurious effects, Mr Francis first digresses into a discussion of follicles, the elliptical transverse section of the human hair (which governs its curliness), its elasticity and non-conductance of electricity. Then he plunges into the abundance of iron in dark hair, the solubility of hair in alkalis, the hair on mummies, and whether or not the hair continues to grow after bodily death. After two pages or so of this, one begins to lose track of what is at issue, but Mr Francis eventually assures us that consideration of these things is necessary “to form a more just estimate of the care and contrivance expended by the Great Artist in producing that which man rejects by the custom of shaving.” He goes on:

“That an appendage so elaborately produced, and possessing such peculiar properties has been intended for the benefit of its possessor, it appears to the writer impious to deny. Among these benefits, according to his experience, are the following:- It keeps the throat and face warm and comfortable in winter. It protects the salivary and other glands from the chilling east winds that prevail so long in our spring. He has found great immunity from sore throat, tooth, or face-ache, to which he was subject while he shaved. It is also maintained by some persons, that through sympathy with the facial nerves, the eyesight is better preserved. In summer also, to his agreeable surprise, he found that, when heated by exercise, the beard caught the perspiration, and thereby forming a greater extent of evaporative surface, cooled the face. The parts covered by the beard are also protected from the action of the sun’s rays, as by a shady grove, aided by its non-conductibility of heat. The moustache he has also discovered to have an important function; when the nostrils are assailed by an offensive odour, the lip instinctively turns up, the hair is thereby applied like a stopper or sieve on each nasal aperture, and the lips being at the same time closed, the breathing is effected through the moustache (and we can breathe in that manner for a long time); the result is, that the perception of offensive odour ceases, or is at least greatly diminished.”

Mr Francis isn’t sure whether the cause of this is mechanical or electrical, but it definitely works, he tells his readers, as he first discovered “in an offensive back passage of a large city some years ago.” This being the case, he argues, might not a moustache save a man’s life – if he were suddenly enveloped by a deadly vapour, say? Worth thinking about before a shave!

Still under the heading of injurious effects, the rejection of the beard has aesthetic implications:

“Although the eye, when visited by custom and false taste, may not perceive it, the appearance of the beard is good and appropriate. It has a severe and manly grace, conveying an idea of dignity and power. It forms a characteristic distinction between his face and that of his gentler weaker partner. Each gains by the contrast; the woman is more womanly, the man more manly. A shaven man is incomplete, shorn of his full individuality. He is a clipt coin, some nineteen shillings in the pound! He is not a man in his full integrity. A man’s beard is always in exact harmony with his peculiar temperament or idiosyncrasy, with his age and character. In youth, slight and downy, it increases in strength and fullness with his developed manhood, and is venerable and beautiful in the silvery hairs of the aged man.”

The greatest artists were bearded, and whenever they sought to represent the Almighty in their works, did they not depict Him as venerable and bearded ?

Mr Francis now launches into a history lesson: the Normans compelled the Saxons to shave, to distinguish them from the Danes; shaving became fashionable in England under Charles II; and “the best king the French ever knew” (Henry IV) was bearded, whereas that “worthless lad” Louis XIII wasn’t. Need we say more?

Next, Mr Francis leaps to the defence of the moustache:

“The moustache has as much expression as the eyebrows – nay, more; for while the latter are comparatively fixed and rigid, the former moves with the lip, and this, from its extreme mobility and sensibility, is a great source of expression in the language of feeling; curling with scorn, compressed with hatred, pouting with anger, it changes with every ripple of sentiment; to which the moustache gives a larger index, and makes the movement more obvious; while the flowing length of the beard confers an air of gravity and dignity. Shaving utterly rejects all this, and is therefore erroneous in taste.”

Finally, we come to the proposition that shaving is immoral in principle. The argument here is that is self-mutilation. What would you think of a man who cut off his nose “with the idea of improving his face”? Not a lot. Not only would it be just plain silly, but it would be “an ungrateful rejection of that which was benevolently bestowed by the Author of nature.” What, then, of the man who shaves off his beard with the same aim?

Of course, one may trim the beard, just as one may trim the nails. It is only total rejection which is immoral. By analogy, it is one thing for a woman to wear her dress a little longer or a little shorter, and quite another for her to wander round with no dress at all!

Mr Francis closes his tract with the earnest hope that there will come a time when “men shall once more be not ashamed to look manly”, when they shall wear their beards proudly, as God intended them to – God, “by whom the very hairs of our head are counted, and without whose permission not a sparrow falls to the ground.”