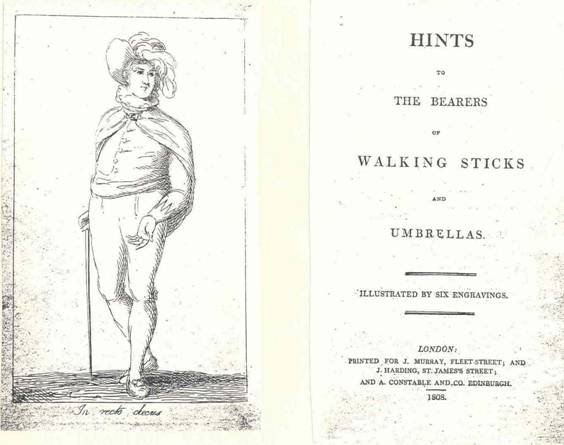

This curious little tract opens thus:

“Similar wants have, in all ages and in all countries, given rise to similar inventions. The Walking-Stick is a contrivance probably coeval with human infirmity; and it is very likely, that Adam, when weakened by accidental injury, by sickness, or by age, might at first have leant on the arm or shoulder of Eve, but when she was absent on family affairs, the Father of Mankind contrived the Walking-Stick. He observed, no doubt, that a slender staff, when pressed in a perpendicular direction, would sustain a weight, one thousandth part of which would break it, if applied transversely. If Adam (as some have supposed) was taught by angels in Paradise as much as it is permitted that man should know of all science and its application to art, and more than his descendants have since invented, he could probably demonstrate mathematically, that a strait stick was, for purpose of support, preferable to one that was crooked.”

Our author next proceeds to demonstrate the antiquity of the walking stick or staff by reference to the Book of Exodus and the works of Virgil and Juvenal, arguing that the staff, the sceptre of the monarch, the spear of the warrior, the crook of the shepherd, and the wand of the magician, are members of the same family of devices.

As to the umbrella, this was invented in the distant past by the Chinese, and was known to the Hindus and the Greeks in antiquity. The inspiration for its invention was possibly the large leaves attached to the branching extremities of a bough.

The umbrella was apparently a rarity in England only fifty years before our author’s time, and as such was an object of obscurity and even ridicule:

“It is recorded in the life of that truly venerable philanthropist, Jonas Hanway, the friend of chimney sweepers and the foe of tea, that he first ventured to brave public reproach and ridicule, ever levelled against innovation with a rancour nearly in a direct ratio to its public utility, by carrying an umbrella in the street.”

Thus far the history of the walking stick and umbrella. Our author now gets down to the main business of his tract, which is an analysis of “the various modes of miscarrying Walking-Sticks and Umbrellas, to the general annoyance of all passengers in the streets.”

Anyone who has ever walked down a crowded street, our author notes, has at some time or other “met with considerable obstruction and annoyance from the awkward manner in which the greater part of mankind carry both Walking-Sticks and Umbrellas.” There is the man who, without really thinking about what he is doing, “dips his cane into the mud, and then wipes the dirty ferule on the clean dress of the next woman who passes.” As if that weren’t bad enough, there is the man who struts along with his cane tucked under his arm, the ferule sticking out behind him, ready to “impale the eye of one who follows with a brisker step.”

After two and a half pages of complaints, our author next expounds three axioms and two propositions on the subject of walking with a stick or umbrella. Axiom 1 states that a man walking quickly incommodes others less than one walking slowly. A corollary of this is that a stationary pedestrian is a positive menace. Axiom 2 states that a man bearing a stick takes up more room than a man without one; axiom 3 that a stick affords secure support only when held perpendicularly. Proposition 1, which is demonstrated with a little diagram that looks like something out of a geometry text-book, states that a man who frequently turns round takes up at least twice the space of one who doesn’t. Proposition 2, illustrated by what looks like an Egyptian hieroglyph, is that a man leaning on a perpendicular stick takes up one-and-a-half times the space of a man with no stick.

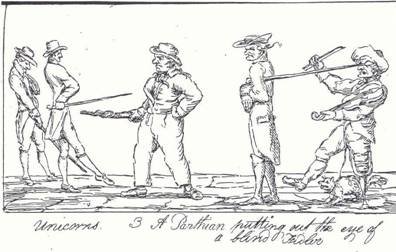

Having established an axiomatic structure for a science of carrying a walking stick, our author next proceeds to detail seven types of offenders. For example, there is the Twirler. This is usually a youth who, in the quest of easy nonchalance, whirls his stick around, and either knocks someone’s hat off, or throws dirt over a passer-by. “Men-milliners, linen drapers’ apprentices, and bankers’ and attornies’ clerks, are commonly Twirlers”, we are told. Then there is the Parthian:

“The Parthian, as every body knows, while his horse galloped, shot his arrows with dexterous aim behind him. Thus many fix the head of their cane or umbrella close under the arm, preserving it firm in a horizontal position, or somewhat inclining upwards: hence an inadvertent or dim-sighted follower receives the dirty end in his mouth, or stabs his eye against the pointed ferule, which, like a reverted spear, wound those who follow, instead of those who meet its bearer.”

Then there is the Unicorn. He is the converse of the Parthian, insofar as the stick is carried horizontally, but protruding forwards rather than backwards. This style characterises “the bullying buck, and many varieties of vulgar swaggerers.”

Likewise, umbrella users are divided into four categories, one of which is all-too-familiar to us today: the Shield-Bearer. This is the pedestrian who, usually when it is windy, holds his umbrella down and in front of him, like a shield. He cannot see anyone or anything in front of him, and he takes up nearly the whole pavement, either banging into those he meets or forcing them off the pavement into the gutter. Then there is the Inverter:

“Inverters are those careless beings who present the inside of the Umbrella to the wind, whereby the cover is turned inside out, and commonly much lacerated, while they impede the progress of many a time-pressed citizen, during their awkward attempts to re-arrange it.”

Our author concludes his tract with the following notice:

“N.B. As the best remedy for the above grievances, I propose to open an Academy, at the Lyceum, in the Strand, for the purpose of drilling Ladies and Gentlemen in the most approved method of handling Walking-Sticks and Umbrellas, with a view to individual grace and general convenience.

The favours of the Nobility and Gentry are humbly requested by their most devoted, &c.

SOLOMON SUPPLEJACK.”

Solomon Supplejack’s real name was, apparently, John S. Duncan, and it is a pity that he is not still around today to write a similar axiomatic treatise on the mis-use of prams and supermarket trollies….