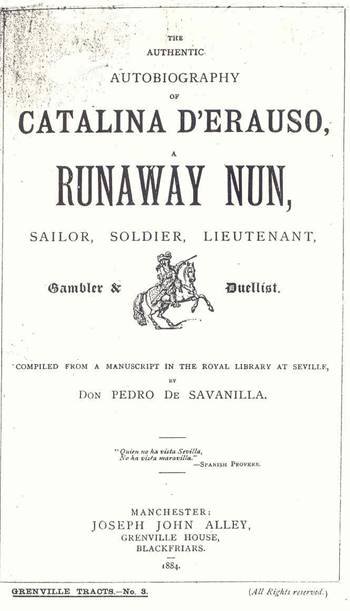

This is another Ripping Yarn for those readers who enjoyed the story of the Aztec Lilliputians.

Catalina d’Erauso was born at San Sebastian in Spain in 1592. On account of family poverty she was deposited in a Dominican convent whilst still an infant. Here she is said to have been “the most unbearable of children”. As she grew up she became “the most turbulent novice in the house”, so that it probably came as something of a relief to the Mother Superior when, in March 1607, she stole the convent keys and escaped.

Straight away she adopted the guise of a man, for she explains how she cut up her habit to make breeches and a coat, and how, cropping her hair short, she found she could easily pass for “a handsome boy.”

Within a short time she had been engaged as a page to Don Carlos de Arellano, but she had to decamp when her father appeared on the scene to explain his daughter’s escape from the convent – Don Carlos being an important patron of it. Thereafter she fell in with some muleteers, and on arriving at San Lucar in Andalusia, she signed on as a cabin boy on a ship bound for South America. Unfortunately, somewhere off the coast of Peru:

“The ship struck a rock, sprang a leak, and was deserted by all the crew, who took to the boats, and unfortunately were drowned. The Captain and myself alone remained. We formed a raft, on which I bound a parcel containing about a hundred crowns in gold, which I obtained by breaking open the money chest with an axe.

The poor Captain fractured his skull against a rock in attempting to reach the raft. I was more fortunate, and reached the land, insensible certainly, but the warm sun revived me.”

On reaching civilisation she next got a job as a tailor’s assistant, but ended up stabbing the cousin of one of her customers, Doña Beatrix de Cardenas. This landed Domingo – as Catalina was now calling herself – in the town jail, but she was helped to escape, disguised as a woman (!), by Doña Beatrix, who had fallen in love with her (thinking her a him), and wanted to marry her/him. Things were getting a bit hot, in more ways than one, so Catalina headed off out to sea in a stolen rowing boat.

She was eventually picked up by a galleon en route from Panama to Concepcion, and gave her name as Pedro Diaz of San Sebastian. On arrival at Concepcion, by yet another singular coincidence, she was introduced to Miguel d’Erauso, her own elder brother, who was Secretary to the Governor General there. Not that it mattered – he had left Spain for America when she was only two years old, so he didn’t recognise her.

It was at this stage of her career that Catalina took part in many expeditions against the Indians. When the Spanish flag was captured by the Indians at the battle of Valdivia, it was she who retrieved it by splitting the skull of the Indian who had carried it off with her sword. For this act of bravery she was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. “In this rank I much distinguished myself,” she wrote, “especially in the famous battle of Puren, in which I fought in single combat, a celebrated Indian chief named Quispigaucha and took him prisoner.”

As a soldier, she took to gambling, and one evening was forced to stab a sore loser through the throat. But as she was “not the aggressor, and had fought fairly, no proceedings were taken concerning it.”

Soon after this, Catalina got involved in a duel which had tragic consequences:

“Juan de Silva, a friend of mine, also a lieutenant, came to me to request my services as second in a duel he was to fight that night with Francisco de Rojas behind the convent of San Francisco. The altercation, whatever it was, had been serious, and delay was inadmissible. I at first declined, but Don Juan saying he would go alone, and if he fell his blood would be upon my head, I was much affected, as I was attached to de Silva, and at length consented to go to the rendezvous. We met a ten o’clock on a dark and sultry night, each with a white handkerchief bound on his arm, and crossed swords; after a few passes each staggered and fell, and at the same moment the seconds, inspired by simultaneous fury, rushed on each other. I almost immediately felt my sword strike home, and my adversary fell, crying “Ah, traitor, you have killed me!” At this moment a frightful flash of lightning blazed in the heavens. By its glare I saw three bodies on the ground, and fell insensibly on the corpse of Miguel d’Erauso, my brother, slain by my own hand!”

Some readers may by now be getting a bit sceptical about this “authentic autobiography”. It’s that “frightful flash of lightning” that does it, plus the fact that our heroine bumps into members of her own family with alarming frequency. But we are assured that the story is for real – the original manuscript is supposed to be in the Royal Library of Seville, together with her petition to the King of Spain for a pension. Also a portrait of Catalina, “the Nun-Lieutenant”, is supposed to exist in a gallery at Aix-la-Chapelle, so the sceptics had better just stay quiet while the rest of us get on with the story.

Catalina next fell in with two adventurers who proposed to cross the Andes in search of el Dorado. Unfortunately, the two men died of cold and exhaustion en route, and Catalina herself was rescued by the servants of a lady landowner. This lady had a sixteen year old daughter by the name of Juana, and Catalina’s rank of Lieutenant made her a fine catch of a prospective ‘son’-in-law. So……..

Catalina proposed that the marriage should take place in the town of Tucuman, as she could escape from there more easily than from Juana’s remote home. Unfortunately, in Tucuman Catalina got involved in another fight over gambling, and skewered a Portuguese gentleman – I use the term loosely – by the name of Fernando d’Acosta. This landed her in jail again, condemned to be hanged, mainly on account of the vengeful false testimony of d’Acosta’s cronies. She writes:

“I was at a loss how to act. If I declared my sex, would this prove my innocence of the murder? Might not such a confession cause further enquiries into my former life, and place me in jeopardy for the death of Miguel d’Erauso? Might not the Inquisition take charge of me as a lapsed nun? What should I gain by exchanging the gibbet for the auto da fe? – the rope for fire and the stake?”

It was a tricky situation, to be sure. A week later she found herself on the scaffold, where she good naturedly tied the hangman’s noose for him. Just as the lever was about to be pulled, into the town square rode a horseman with orders to postpone the execution. Apparently the witnesses who had testified against Catalina had been arrested, and had admitted giving false evidence. The death of d’Acosta was adjudged to be not murder but, as we would now say, justifiable homicide. Eventually she was acquitted and freed.

As for the lovely Juana, a friend of the family decided that the scandals surrounding her ‘fiancé’ were a bit much, even if ‘he’ was innocent. The wedding was accordingly off, and Catalina was shown the way out of town in no uncertain terms. Needless to say, she didn’t argue for once.

Catalina’s next major adventure was in Cuzco, Peru. Here she was involved in a somewhat confusing series of events, the upshot of which was the abduction of one Doña Maria de Chavarria, not to mention the death of her husband Don Pedro in yet another sword fight. Catalina, now posing as Don José de Salta, a native of Biscay, was herself wounded in the fray. Her need for a surgeon on this occasion, plus the fact that the scandals of Tucuman were still very much in the air, meant that Catalina’s situation was now trickier than ever. Accordingly she threw herself on the mercy of the Bishop of Cuzco, confessing that she was really a woman. “The surprise of the Bishop may be imagined,” she wrote. “Help was called for, and a surgeon came, who corroborated my confession.”

Naturally the Bishop wanted to know the full story, and he sat “in silent amazement” for a full three hours whilst Catalina told of her adventures, from her escape from the convent at the age of fifteen, to the recent sword-fight in Cuzco. “It is true,” she concluded, “that I have committed many crimes. I have killed; I have wounded; I have lied, cheated and stolen; yet amidst all these disorders, I have remained an unsullied virgin, as on the day when I was born.”

With the Bishop’s help she was pardoned of all crimes (apparently more or less on the basis that she was an ex-nun!) and on November 1st 1624 she arrived back in Spain, where she was granted a pension by the King. A little later she made a pilgrimage to Rome, where she was granted a special interview with Pope Urban VIII. “I narrated my adventures,” she wrote, “and being much inconvenienced by excessive curiosity, obtained permission from him to wear male attire for the rest of my life.”

The autobiography ends here, but not the tract, for a conclusion has been added to the story, which reads as follows:

“Our heroine was at Corunna, in Spain, in 1635, and embarked thence for America. Nicolas de Renteria, a Capuchin monk, was on board the same vessel, and gives some account of her, saying that she wore male attire and bore the name of Antonio d’Erauso.

The vessel anchored in the roads of Vera Cruz, and it was a dark and stormy night when the Captain, several Officers, and the Monja Alferez ventured towards shore in the ship’s long boat. On arriving at the hotel they noticed Catalina’s absence. She failed to appear. Whether she fled to the interior of the country, to resume her wandering life, or whether she was drowned in attempting to land in the darkness of a tempestuous night was never known.”