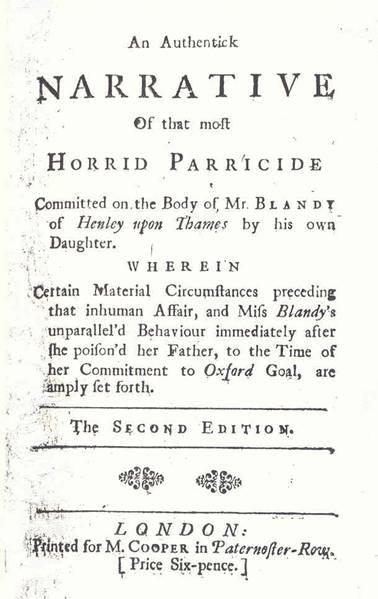

Mary Blandy was a well educated and “very agreeable young lady”, who was “the sole Delight of her indulgent and tender Father.” Up until the end of 1751 her behaviour “never gave the least Occasion to suspect her Duty to her Parent, or want of Virtue, and Good-Nature.”

Now enter the dastardly Captain William Henry Cranstoun, who was captivated by the lovely Miss Blandy, and took to wooing her. Despite the fact that he had a number of eager rivals for her hand, and, presumably, the rest of her,

“…the Captain had the happy Talent to please her best, and he succeeded so well in her Affections, as to obtain a Promise of Marriage, and confirmed by the most solemn Protestations of inviolable Fidelity.”

Mr Blandy, apparently, was well-pleased with the match, and gave the forthcoming marriage his blessing.

Unfortunately, the gallant Captain had omitted to mention that he was already married to a lady in Scotland, and that he had two children by her. It must also have slipped his mind that some months earlier he had been about to commit bigamy with “the daughter of a certain Leicester-shire Gentleman”, and that on being recognised at a social function by a friend of his wife’s, he had been “obliged to decamp, and make a precipitate retreat.” Unfortunately, too, Mr Blandy found out about all this, and despite his protestations of innocence, called off the wedding and forbade Captain Cranstoun ever to see his daughter again.

The lovely Miss Blandy, however, refused to believe any of it, and despite her father’s watchful eye, she and the Captain managed to exchange passionate letters. Then Mr Blandy found out, and that was the end of that. Miss Blandy was made virtually a prisoner in her own bedroom:

“Confinement to a Lady of Miss Blandy’s Disposition, was worse than Death, and she thought of many Expedients to escape the Tyranny of her cruel Father, for in that Light she look’d upon him in her own Mind. She knew the Captain’s Circumstances too well to fly to him, as Matters then stood; so that which way to avoid the fatal Consequence of her Confinement, and what she termed the Cruelty of her Father, now became the Matter of her more serious Consideration.

Led on by a giddy and headstrong Passion, she form’d the black Design of taking him off by Poison; and tho’ the impious Parricide shock’d her at first, yet the Force of her Affection so far overcame her Reason, that she determin’d within herself to put it into Execution. The flattering Hopes of pursuing her mistaken Happiness uncontroul’d, confirm’d her in her Purpose, and she thought that when her Father was Dead, there would be an End of her Misery.”

To gain the opportunity and avert suspicion she pretended to fall in line with her father’s wishes. This, of course, delighted her father, who, “overjoy’d with this happy change…indulged her in whatever he thought would make Her happy.” Meanwhile, she had had some white arsenic smuggled into the house in a package purportedly containing some buckles.

Miss Blandy’s first attempt to poison her father was a failure. She put some poison in his breakfast tea, but he claimed that it tasted peculiar, and threw it – and the cup, apparently – out of the window.

She next mixed some arsenic with the powder he took to relieve his gout, and this he swallowed without suspicion. Just to be on the safe side, she slipped some more into his water-gruel. I now return to the contemporary account:

“In a short time after he had taken this fatal Potion, the unhappy Gentleman found himself prodigiously disorder’d; and the Servant-Maid in the Interim, drank off what Gruel was left, and was likewise much affected thereby. This wicked Wretch pretending great Sorrow at seeing her Father in Pain, asked where his Disorder lay; he told her in his Bowels, and that his Pains increased more than he was able to bear. Upon this she told him, that She imagin’d it was the Gripes, and advised him to take some Daffy’s Elixir. The unhappy Gentleman, ignorant of the Cause of his Disorder, readily accepted the Medicine, and drank off a large Glass of it.

The Barbarity of this Circumstance is extremely shocking! She knew the hot Quality of that Elixir, and the terrible Effects it would produce on one who had already taken more than sufficient of a fiery Poison to deprive him of Life. He had no sooner drunk this cruel Remedy, than he fell from his Chair in the most violent Agony, and swell’d prodigiously. Assistance being call’d, the most proper Antidotes were apply’d, but this inhuman Creature being very officious in the Management of them, by her Contrivance they had not the desired Effect.

He lay in the most lamentable Tortures for the Space of Forty-Eight Hours without Relief; a Physician came Post from London, and all possible Means made use of, but in vain, for his Body swell’d to that Degree that it burst, and he died a most shocking Spectacle to behold.”

Miss Blandy was quickly suspected, and it wasn’t long before a quantity of white arsenic was found in her Dressing-Box. When asked what it was for, she replied that it was for cleaning her jewels. A little later she changed her story and said that she had been given it “as a present from her admirer”, and that he had told her it was Love-Powder.

Miss Blandy was sent to Oxford Gaol to await trial. Whilst there she was asked how she could have committed such a terrible crime. She replied that “she did not think there was any Crime to dispatch a cross old Fellow out of the way, who was the only Bar to her Happiness, and that she would do it, was it to be done again.” It would appear, then, that she and Captain Cranstoun were quite well matched after all.

Her trial, which gave her “very little concern”, began on the 29th of February 1752 at Oxford Assizes. She pleaded not guilty, but, not unexpectedly, the court found otherwise, and she was hanged on the 6th of April that year.

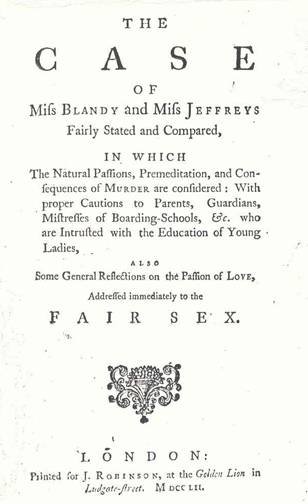

The case of Miss Blandy attracted much attention at the time, and we now turn to another tract which compared her case to that of another murderess, Miss Jeffreys. It was entitled The Case of Miss Blandy and Miss Jeffreys Fairly Stated and Compared, in which the Natural Passions, Premeditations, and Consequences of Murder are considered; With proper Cautions to Parents, Guardians, Mistresses of Boarding Schools, &c, who are Intrusted with the Education of Young Ladies, also Some General Reflections on the Passions of Love, addressed immediately to the Fair Sex. No author is stated, but it was printed for J. Robinson in 1752. Its title page is reproduced below.

Before we reflect upon the Passions of Love and the advice to those entrusted with the care of Young Ladies, I had better satisfy my readers’ curiosity as to who Miss Jeffreys was.

It is a lurid tale. Elizabeth Jeffreys lived with her Uncle, and apparently had a long-standing incestuous relationship with him. On this account, she was led to expect that she would inherit his money when he died. But the appearance of another woman on the scene put this cosy little arrangement in jeopardy. Miss Jeffreys, who had meanwhile taken a lover called John Swan, decided not to give her Uncle even the chance of transferring his affections – and more particularly his fortune – to another woman, so she stabbed him to death. Unfortunately, this simple and effective plan had one drawback – it landed her on the gallows on March 28th 1752, only days before Miss Blandy.

Miss Jeffreys was less well educated and of a lower social class than Miss Blandy, but as our author notes, both demonstrate “that whether in high or low Life, when once a Woman has shook off her Feeling, the Tyger, in his Nature, is not more ferocious than she.”

But let’s get down to some advice to those in charge of young ladies. Our author writes:

“I shall conclude my present Design with a particular Desire, that all they to whom the Education of young Ladies is intrusted, would be careful to implant Principles of Virtue early in their Minds, to teach them a Contempt of Flattery, and especially to conduct them with Safety thro’ the fair Regions of Love, from whose Universal Tyranny more Calamities flow, than any other Cause that subsists in Nature; for, as Love is the most violent, so it is the most universal Passion, that reigns in the human Breast, and deserves to have its Spring and Progress narrowly watch’d; lest by fixing our Affections on Objects unworthy of them, or of those Merits we are incapable to judge, that generous Flame should glow for unnatural Gratification, and the soul be stained with guilty Wishes.”

As for the advice to the young ladies themselves, the following remarks would perhaps today be misconstrued as a bit on the chauvinist side by some of the more liberated ladies of today:

“To my fair Readers, I would at present make an immediate Address; and the Pen of one who has been long devoted to their Service, cannot be suspected of offending their gentle Natures. The Passions of the Ladies are allowed to be stronger than those of the Men; their Modesty greater, and their Experience less. They are condemned by their Delicacy to more Solitude; they see not the Bustlings of the World, and the Snares of Artifice; they are harmless and unsuspected in their Tempers; they easily believe Professions; they mistake Compliment for Passion, and are prepared by Emulation to give Ear to Flattery, and to imagine that they really profess the Graces the designing Lover endeavours to describe.”

He goes on:

“Natural to the Sex is an Anxiety for Wedlock; antiquated Virginity is dreadful to contemplate; and as they are debarred by Modesty from making Advances, so they are apt to credit false appearances, and to give away the Heart to the earliest Solicitor.”

For this reason young ladies are urged to consult their parents as soon as “Love first warms the Bosom.”