Fig. 7.1

In the field of Independent Thought one is never very far away from either the Great Pyramid or Atlantis, and in the present chapter we’re rather afraid that we must grapple with the first of these yet again. This time we follow Michael W. Saunders, an electronics engineer from Chaldon, Surrey, in his fascinating attempt to reconstruct from the monuments of past ages the memory of an extraterrestrial visitation.

But this is not the usual run of von Dänikenish intervention. Mr Saunders’ ideas are an altogether more ingenious and sophisticated kettle of fish, with an intriguing mathematical background to boot.

Mr Saunders’ basic approach to ancient monuments was well illustrated by his excellent little book Destiny Mars, first published in 1975. This was later augmented by two other booklets, Pyramid Mars Connection (1976) and Extraterrestrial Databank on Phobos (1976).

But Mr Saunders does not just deal with the Great Pyramid in Egypt. His theory also involves the giant pyramid of the Americas, the so-called Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan, in central Mexico.

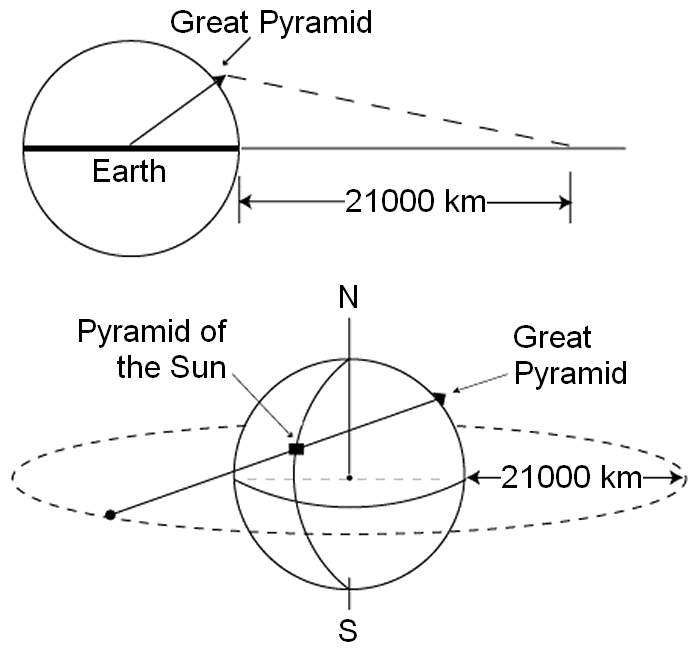

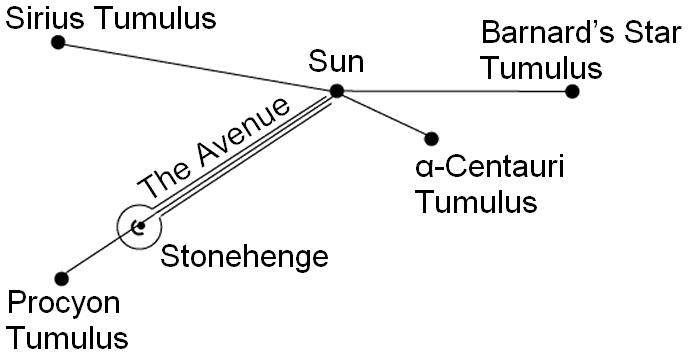

He discovered two things. Firstly, that the north face of the Great Pyramid, if extended into space, met the plane of the Earth’s equator at a height of just over 21,000 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. Secondly, that a line joining the Great Pyramid to the Pyramid of the Sun, when extended, met the equatorial plane at very nearly the same height. Both these ideas are illustrated in Fig. 7.1.

Fig. 7.1

Mr Saunders concluded that these two great pyramids could hardly be so related by accident, and he postulated that they had been designed to indicate a particular orbit in the plane of the Earth’s equator, and at a height of 21,000 km above it. But an orbit for what?

At first he thought it might be an alien time-capsule, a satellite containing information useful to an earth civilisation capable of interpreting the pyramids correctly, and of retrieving such a satellite from its orbit. But it was pointed out to him, by Duncan Lunan, that such a satellite must have been put into orbit many centuries ago, and that the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon would long since have disrupted its orbit. Mr Saunders agreed with Mr Lunan, and began to think, instead, that this orbit was probably only an “intellectual signpost”. That is, it had never actually been occupied by a satellite, but that instead it was meant to indicate in some way the actual location of such a satellite or time capsule elsewhere in the Solar System. The Pyramid Orbit was just a hint of something bigger.

It was Mr Lunan who noticed that if a satellite were to move around the Earth in such a pyramid-indicated orbit, then it would complete one revolution every 0.515266 days (its sidereal period), and that this period of time was very close to half a Martian day.

Furthermore, the height of this pyramid-indicated orbit, 21,000 km, was close to the equatorial circumference of Mars.

Here already were two striking indications of the planet Mars. Accordingly, Mr Saunders studied the Great Pyramid even more closely, and was gratified to find even more pyramid–Mars connections.

For example, he found a link between the Great Pyramid and the two tiny moons of Mars, Phobos and Deimos.

During the time it takes the Earth to rotate once on its own axis, Deimos does nearly π/4 revolutions around Mars, whereas Phobos does nearly π revolutions. The slope of the Great Pyramid, as is well known, seems to be based on π as well, so that the Great Pyramid and the Martian satellites are linked via this universal constant, the ratio of the circumference to the diameter of a circle.

Again, the entrance to the Great Pyramid is not exactly half way along the northern face, but about 0.53 of the way across instead. And it so happens that the equatorial diameter of Mars is about 0.53 times that of the Earth.

Finally, the principal chamber of the Great Pyramid (the King’s Chamber) is displaced from the central axis of the structure by an amount which Mr Saunders claims is representative of the displacement of the Sun from the geometrical centre of the orbit of Mars.

From these observations and others, Mr Saunders concluded that the two pyramids and their indicated orbit were a significant signpost to Mars, and by various ingenious methods he set about finding potential locations for his hypothetical time capsule.

The most promising of these was on the satellite Phobos, and by an convoluted argument involving pyramids and volcanoes, Mr Saunders claimed to have determined its theoretical position to within 10 metres. Retrieving it – or even verifying its actual existence – was quite another matter, of course.

In 1975, when Destiny Mars first appeared, NASA seemed to be neither impressed by nor even mildly interested in Mr Saunders’ predictions, but in 1976 and 1977, photographs of Phobos were taken by the Viking orbiter craft for the purposes of compiling a map of its surface. The photographs did not reveal any unusual features at or near Mr Saunders’ predicted site, but then Mr Saunders was not really surprised by this. Such a databank would have been well hidden anyway, to minimise the chances of accidental discovery. Consequently its location would have been made to look like any other part of the surface, and so we could hardly expect to spot it even on a close-up photograph.

But let us return to Earth.

After this intriguing reinterpretation of the Great Pyramid and the Pyramid of the Sun, Mr Saunders turned his attention to Stonehenge.

Now, if one looks at a plan of this monument, it is not at all difficult to imagine that the various rings of stones and holes may represent planetary orbits, and this was the basic idea that Mr Saunders set out to explore in his book Stonehenge Planetarium (1979).

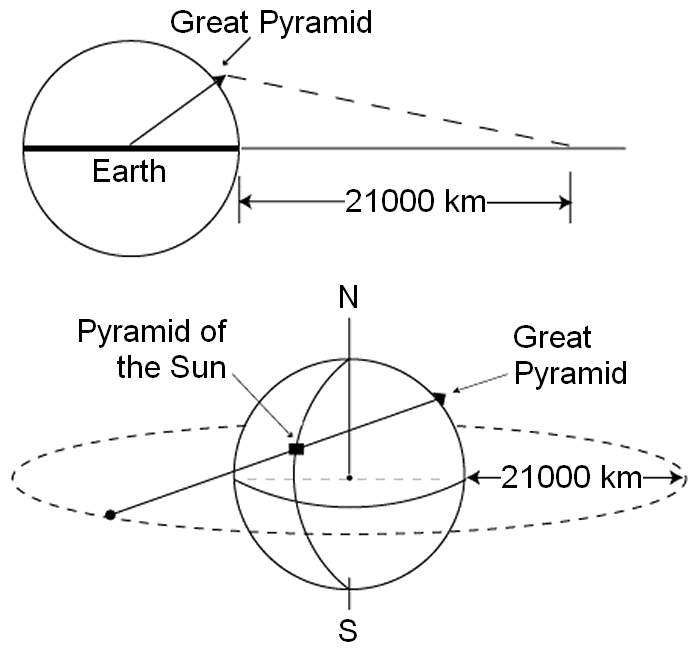

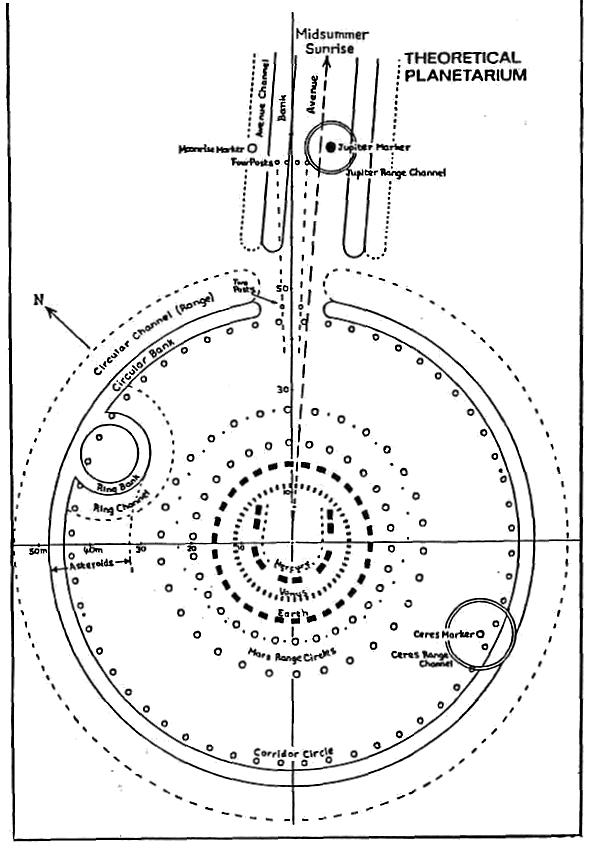

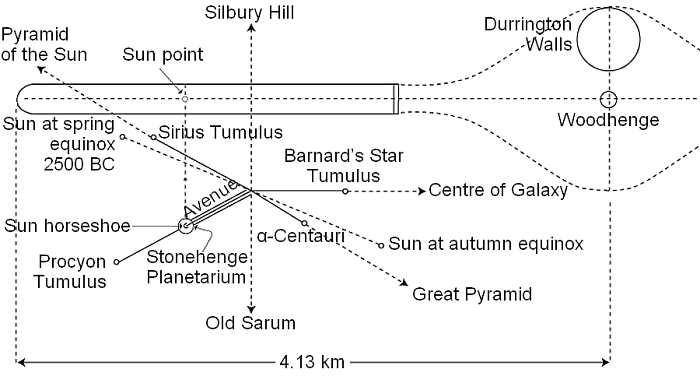

We reproduce two of Mr Saunders’ diagrams here (Figs. 7.2 and 7.3) as they form a convenient platform from which to discuss his theory.

Fig. 7.2

Fig. 7.3

The first point which immediately strikes one about the Stonehenge model of the inner planets is that this can be no ordinary planetarium. Inside the circular asteroid bank there are two horseshoes of stones (the Bluestone Horseshoe and the trilithon Horseshoe), two circles of stones (the Bluestone Circle and the Sarsen Circle), and three circles of filled in holes (the Y holes, the Z holes and the Aubrey holes). That is, seven ‘rings’ of one sort or another.

Now, unless one accepts Velikovsky’s theory that planets can come and go within the solar system, then these seven rings are a few too many for the four inner planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars.

Then again, if this is a model of the solar system, why are there horseshoes as well as circles of stones? And why are the circles and horseshoes of stones of different heights as well as compositions? If Stonehenge is a planetarium, then all these things must symbolise something.

According to Mr Saunders, they do indeed represent planetary attributes, but before discussing some of them, let’s explain why there are seven rings to only four inner planets.

The Stonehenge planetarium, Mr Saunders calculates, represents the solar system on a scale of 1 in 10,000 million. The Bluestone Circle represents the orbit of Venus and the Sarsen Circle that of the Earth. The Y and Z holes represent the minimum and maximum distances of Mars from the Sun. The Aubrey holes relate to the orbit of Ceres, the largest of the asteroids, and the Bluestone Horseshoe to the orbit of Mercury. Next the Trilithon Horseshoe. This represents the Sun, not on the same scale as before, but on a new scale of 1 in 100 million. The reason for this change of scale, Mr Saunders explains, was because if the builders had put the Sun in the middle on the same scale as the orbits, it would have been a little stone about 7 centimetres in radius, which might have got displaced or even lost. Actually, for reasons of space, we’ve rather simplified Mr Saunders’ theory, and anyone who is puzzled by the uses of rings of holes and horseshoes of stones, should refer to Mr Saunders’ book for details. As to the Outer Planets, if these had been represented on a scale of 1 in 10,000 million like the Inner Planets, then they would have entailed enormous circles of stones and holes which would have been quite impracticable. Consequently, Mr Saunders believes that these were given only a single token representation. Thus, the so-called Heel Stone represents the mean Jupiter–Sun distance, and the length of the so-called Avenue represents the mean Pluto–Sun distance. Unfortunately, there is no trace today of anything that might once have represented Saturn, Uranus or Neptune, but Mr Saunders is quite sure that they were once there.

Having explained the basis of the planetarium, we must refer the interested reader to Mr Saunders’ booklet for further details.

Now, let us just pause for a moment to consider what all this rather sophisticated astronomy means. Either the whole thing is a mare’s nest from start to finish; or the ancients were vastly more sophisticated than we today give them credit for; or, the ancients were not that sophisticated, and had outside, extraterrestrial help.

Discounting the first explanation as altogether unworthy, let us consider the other two possibilities. Thanks to the likes of Gerald Hawkins and Alexander Thom, we now know that the ancients were a lot more accomplished in astronomy than we tend to give them credit for. On the other hand, the Great Pyramid Indicator and the Stonehenge Planetarium, are, if Mr Saunders is correct, altogether too clever. Which implies something like an extraterrestrial intervention, but why?

We saw earlier that Mr Saunders interpreted the Great Pyramid as a signpost to a time capsule or databank that would be of use to a civilisation developed enough to interpret the monuments correctly and retrieve the capsule.

Stonehenge could well have been a sort of extraterrestrial visiting card, as Mr Saunders explains:

If there have at some time been visitors to the solar system, it could be reasoned that they might have installed something that would reach the attention of, for instance, an advancing, yet conservation minded, society.

The message is reinforced even further by the relationship which exists between Stonehenge, the Great Pyramid and the Pyramid of the Sun. For, taking Stonehenge as the Solar System, and retaining the scale of 1 in 10,000 million, then the Great Pyramid represents the star Alpha Centauri, and the Pyramid of the Sun the star Sirius. Or more precisely, their positions in 2500 BC. Why these two stars in particular? Probably because Sirius is the brightest star in the sky and Alpha Centauri the nearest.

In The Wiltshire Galaxy (1979), Mr Saunders turned his attention to Salisbury Plain and the proliferation of tumuli and long barrows that surround Stonehenge. These – or at least some of them – Mr Saunders sees as representations of the stars in the immediate vicinity of the Solar System.

The scale, of course, has to change from that of the planetarium itself. We have already seen that on a scale of 1 in 10,000 million, Alpha Centauri, the nearest star, is way over in Egypt. If we are to get a local star map to fit on Salisbury Plain then clearly we have some adjusting to do.

After due deliberation Mr Saunders deduced that the new scale of representation was 1 in 119 million million, this being deduced from a consideration of the length of the Stonehenge Avenue, or, more precisely, the length of that portion joining the centre of Stonehenge to the first sharp bend of the avenue. It is this bend, incidentally, that represents the Sun in the star model, and not Stonehenge proper.

The star map that emerges is shown in Fig. 7.4. Of course, we are looking at a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional array of stars, but nevertheless, Mr Saunders claims, these tumuli roughly summarise directions from the sun as well as representing their distances from it.

Fig. 7.4

But there is more to come. Sirius is a binary star. That is, it consists of two separate stars, each revolving around the other, and Mr Saunders claims that this is actually shown by the tumulus which represents Sirius. For the outer radius of this tumulus, 26 metres, represents the distance between the two components of Sirius on a scale of 1 in 119,000 million. If this figure looks vaguely familiar, it should do – it is precisely 1000 times the scale of the basic star map.

The Alpha Centauri tumulus, to the same scale, likewise represents the separation of the two main components of Alpha Centauri to tolerable accuracy.

But what of the Wolf 359 tumulus? If we apply the same reasoning then it follows that this too has a binary component at something like 14 Earth–Sun distances. To date, no astronomer has ever had any reason to suspect that Wolf 359 has a second component at all, so that Mr Saunders is rather putting his money where his theory is, and making a rather fascinating prediction for the future.

The tumulus star model theory likewise indicates a companion for Barnard’s Star, and this is interesting because some astronomers have suggested that Barnard’s Star has at least one something revolving around it.

Nor have we exhausted the message of the Salisbury Plain tumuli. Fig. 7.4 is only an ‘inset’ into a map of the entire galaxy, with Woodhenge representing its centre, Durrington Walls Enclosure part of the bulging nucleus and the long linear earthwork known as the Cursus representing the plane of the spiral arms. Fig. 7.5 will make this clear.

Fig. 7.5

As can be seen, the Stonehenge ‘inset’ is placed vertically below the position occupied by the Sun in the spiral arms, and of course, the galactic representation is on a different scale to that of the localised inset. Fig. 7.5 is on a scale of 1 in 100,000 million million.

To sum up, then, the Wiltshire Galaxy begins as a side-on picture of the Milky Way, into which is inset a map of the stars in the immediate vicinity of the Sun, and into which, in its turn, is inset the Stonehenge Planetarium itself.

It is an extraordinary and ingenious theory, even if one is left wondering about the hundreds of tumuli on Salisbury Plain that don’t figure in Mr Saunders’ stellar maps.

Curiously, at about the same time that Mr Saunders published his Stonehenge Planetarium, two Russians called Vladimir Avinsky and Valentin Tereshin were proposing a rather different planetary theory of Stonehenge.

We had a great deal of trouble getting to grips with this theory because every reference to it in English was rather vague. Eventually, though, we got hold of a curious document consisting of three pages of pidgin English, one of pure Russian and a poorly explained diagram to boot. The following, then, is what we think the Russian theory is all about.

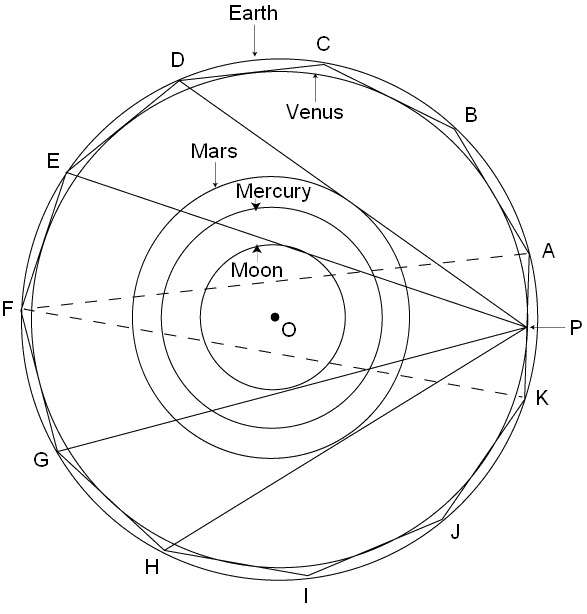

It begins with a rather involved geometrical construction whose end product is a set of concentric circles, each of which represents a planet. Insofar as the Russian theory deals with the sizes of the planets rather than their distances from the Sun, it is a very different planetarium to that proposed by Mr Saunders.

Fig. 7.6

Referring to Fig. 7.6, ABCDEFGHIJK is a regular eleven-sided polygon. That is, all its angles are the same size and all its sides are the same length. The geometrical centre of this polygon – we call it the 11-gon for short – is at O. It is this point which acts as the centre for the set of planetary circles, the diameter of each circle being in proportion to the equatorial diameter of the planet it represents. Thus, to the same scale, the circles represent the Moon, Mercury, Mars, Venus and the Earth in ascending order of size.

These circles are constructed from the 11-gon as follows. P is the mid point of AK. The Moon circle touches EP; the Mercury circle passes through the point where EP crosses AF; the Mars circle touches DP; the Venus circle touches each side of the 11-gon at its mid point; and finally the earth circle passes through all the corners of the 11-gon, A to K inclusive.

On seeing this scheme for the first time it is tempting to dismiss it as something of a Mickey Mouse construction, and yet it is surprisingly accurate – no more than 1.5% in error.

So where does Stonehenge come into it?

Avinsky and Tereshin claim that the builders of Stonehenge were aware of this remarkable geometrical unity between the moon and the Inner Planets, and that they incorporated it into the ground-plan of Stonehenge.

The Sarsen Circle is the Moon; the Z holes represent Mercury and the Y holes Mars; and, roughly speaking, the inner and outer edges of the surrounding bank represent Venus and Earth respectively.

In the version that we have seen of the theory, there is no mention of the Outer Planets. Furthermore, the two central horseshoes of stones, the Bluestone Circle and the Aubrey Holes, do not seem to be representative of any planet at all. Finally, no reason is given for the use of stones for one planet and holes for another.

Newspaper accounts of the theory published around September 1979 hinted that a “pentagram” was involved in the construction, but this now seems to have referred to the figure PDEGH rather than the traditionally mystical five pointed star familiar to western readers. It was an extension of this pentagram, apparently, which enabled Avinsky and Tereshin to link Stonehenge, the Cursus, Woodhenge and seven long barrows in a marvellous astronomical plan. Unfortunately we haven’t got the details for this, so that we must leave our readers on something of a cliff-hanger here.

But it must not be supposed that all this planetary jugglery with Stonehenge is exclusively a product of the space age. Far from it, and we close this chapter with two other interpretations of the monument which were published in the middle of the nineteenth century.

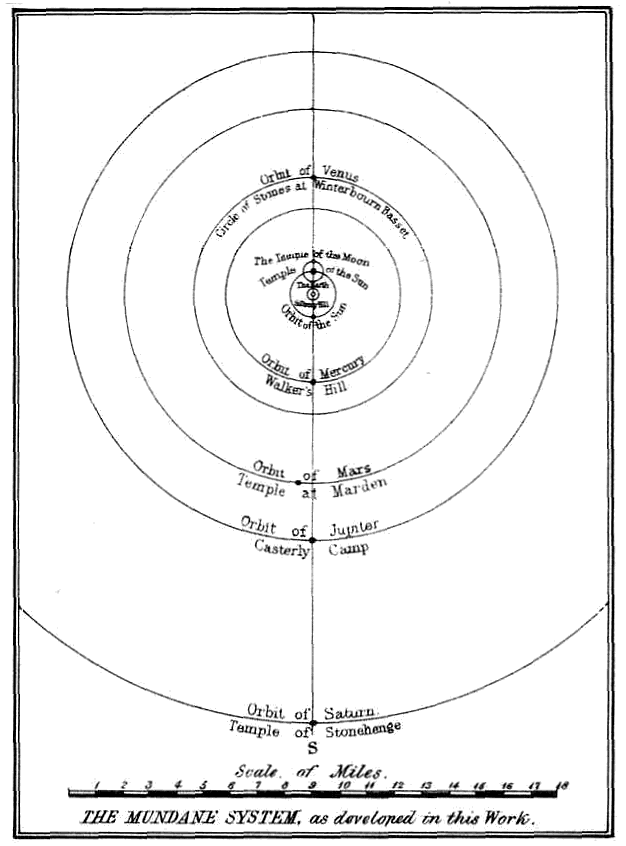

The first of these appeared in the Reverend E. Duke’s little book, The Druidical Temples of the County of Wilts (1846), and is reproduced in Fig. 7.7.

Fig. 7.7

Here is how Rev. Duke summarised his thesis:

My hypothesis then is as follows: that our ingenious ancestors portrayed on the Wiltshire Downs, a Planetarium or stationary Orrery, if this anachronism may be allowed me, located on a meridional line, extending north and south, the length of sixteen miles; that the planetary temples thus located, seven in number, will, if put into motion, be supposed to revolve around Silbury Hill as the centre of this grand astronomical scheme; that thus Saturn, the extreme planet to the south, would in his orbit describe a circle with a diameter of thirty-two miles; that four of these planetary temples were constructed of stone, those of Venus, the Sun, the Moon, and Saturn; and the remaining three of earth, those of Mercury, Mars and Jupiter, resembling the “Hill Altars” of Holy Scripture; that the Moon is represented as the satellite of the Sun, and, passing round him in an epicycle, is thus supposed to make her monthly revolution, while the Sun himself pursues his annual course in the first and nearest concentric orbit, and is thus successively surrounded by those also of the planets, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn; that these planetary temples were all located at due distances from each other; that the relative proportions of those distances correspond with those of the present received system; and that, in three instances, the sites of these temples bear in their names at this day plain and indubitable record of their primitive dedication.

Going from north to south in Fig. 7.7, the temples representing the planets are: Venus (a stone circle in Winterbourne Bassett); the Moon and the Sun (two stone circles within the Avebury enclosure, the easterly one being the Sun; the westerly one, the Moon); the Earth (Silbury Hill); Mercury (a long barrow on Walker’s Hill); Mars (a large tumulus called Hatfield Barrow, near Marden, now destroyed); Jupiter (Casterly Camp); and Saturn (Stonehenge).

The “indubitable” place-name evidence for these correspondences, to which Rev. Duke refers, is clear only in one instance: Marden = Mars-Den = House of Mars. The other two survivals are less obvious. The link between Walker’s Hill and Mercury relies on the fact that a tumulus in the same locality is called Knap Hill, and that Knap = Knoph = the Egyptian equivalent of Mercury. The link between the Sun and the Moon and Avebury is the other, and this one depends on the fact that Avebury = Abury = Abiri = the Hebrew expression for “The Mighty Ones”!

Rev. Duke, incidentally, saw nothing amiss in hopping back and forth from Druid Temples to Egyptian or Hebrew etymology. He was a firm believer in the theory, prevalent at the time, that the Druids (whom he erroneously believed to have erected Stonehenge and the rest of the planetarium) originated in the east, in the same cultural atmosphere that spawned the great civilisations of the Middle East.

Of course, even in Rev. Duke’s day it was generally believed that Stonehenge was a Temple of the Sun, and he stressed that he was not rejecting this popular idea at all. After a careful analysis of the monument, he assured his readers that Stonehenge was really two temples rolled into one – an early solar one and the later Saturnine addition built at the time the planetarium was conceived. The Heel Stone, over which the Sun rose at the summer solstice, was part of the early solar temple, to be sure, but was not the bank of earth surrounding the monument wonderfully representative of the Rings of Saturn? Incidentally, before any of our readers quibbles at this, we would point out that Rev. Duke had watertight evidence that the Druids knew of, and used, the telescope!

The major objection, though, was that Rev. Duke had put the Earth at the centre of the Solar System, that he had the Moon revolving about the Sun rather than the Earth, and that the distances were all wrong.

The good Reverend had a ready answer: “I am not endeavouring to prove what is the true astronomical system, but am only labouring to show what was the system believed in, and actually portrayed on the face of the land by our heathen ancestry, however erroneous that system may have been.”

Finally, the reader might like to know why the Druids placed the planets on a meridional line and in the positions shown in Fig. 7.7. Why did they put Venus, the Sun and the Moon to the north of Silbury Hill, and Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn to the south?

Rev. Duke claims it was because the Druids believed that these were the positions the planets occupied on the day of creation, and that when all the planets returned again to these positions, “the old world would end, and a new world spring into being.”

So much for Reverend Duke. Another planetary interpretation of Stonehenge – not to mention the Great Pyramid and a host of other antiquities – was put forward by Mr John Wilson in his book The Lost Solar System of the Ancients Rediscovered (1856). It came in two volumes, totalling some 960 pages, and is still guaranteed to give its readers a headache within minutes.

By a process that is not at all clear, Mr Wilson deduces that the monuments of the ancient world – nearly all of them, so far as we can gather! – were constructed in terms of a unit of measurement called simply “The Unit”. One unit was slightly over 14 inches in length.

It is an extraordinary book. Straight from the word go, Mr Wilson plunges into a treatise on gravitational attraction, the summation of mathematical series, Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion, and the origins of the shape of the Egyptian obelisk. After an abstruse discussion of Babylonian weights and measures, Chinese junks, and a statue of Peter the Great, he is ready to tackle the mystery of the Great Pyramid, which he does with characteristically incomprehensible gusto:

Since pyramid of Cheops = ½ circumference and cube of Cheops = ¼ distance of moon, Height: side of base of pyramid of Cheops :: 406 : 648 :: pyramid of Cheops: a pyramid having same base and height = side of base. Distance of moon = 4 cubes = 12 pyramids each having height = side of base. So 406 : 648 × 12 :: ½ circumference : 9.57 circumference. Thus distance of moon = 9.57 circumference.

We are not at all sure what Mr Wilson is on about here, but it is definitely to do with planetary distances. We did catch up with him, though, in one of his more lucid moments, so we are able, reliably, to inform our readers that if all measurements are in units, then 1600 times the cube of the base side of the Great Pyramid gives the distance of the Earth from the Sun, and that 5 times the cube of the base side of Chephren’s Pyramid (the second largest at Giza) gives the distance of the Moon from the Earth.

As for Stonehenge, and again stressing that everything must be expressed in units, the cube of 3 times the circumference of the Sarsen Circle gives 6 times the circumference of the Earth; the cube of 10 times the circumference of the Bluestone Circle gives the distance of Mercury from the Sun; and 10 times the cube of 5 times the length of the Avenue of Stonehenge gives the distance of Saturn from the Sun.

And if all that doesn’t clear up the mystery of Stonehenge, then it has certainly added to it!